INTRODUCTION

In the annals of human history, there are epochs, like the Industrial Revolution, that echo through the sands of time, ever reverberating their profound significance. The mid-18th to mid-19th centuries opened humanity to a new realm of possibilities with inventions like James Watt’s steam engine and Eli Whitney’s cotton gin paving the path towards modernization. The Industrial Revolution was not just an era of enhanced machines—it was the very dawn of the Modern Age, an unruly child of invention, imagination, and iron. This dramatic shift from agrarian and handicraft economy to one defined by industry and machine manufacturing changed how we live, travel, and interact, reaching every corner of societal infrastructure.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

What we now know as the Industrial Revolution began in Britain in the mid-1700s, fueled by an abundance of coal and iron ore—key ingredients for the production of the goods and services which would redefine human society. A legion of inventors and innovations emerged to create machines such as the flying shuttle, power loom, and spinning jenny, transforming the textile industry, among other sectors, and giving birth to modern, large-scale manufacturing.

Simultaneously, remarkable advancement in steam technology—the most notable being James Watt’s 1775 steam engine—served to escalate industrial productivity substantially. The impact resonated far beyond Britain, and by the mid-19th century, much of Western Europe and the Eastern United States had been enveloped by this monumental wave of change.

THEORIES AND INTERPRETATIONS

Historians peering into the machinery of the Industrial Revolution have spun multiple theories about its causes and implications. Economists like Nicholas Crafts and Knick Harley endorse the “Bourgeois Revolution” theory, crediting a rise in the social status and aspirations of the middle class as the driving force. In contrast, Robert C. Allen attributes the Revolution to unique economic conditions in Britain—affordable coal and high wages that incentivized mechanization.

Some historians view the Revolution through the lens of Neo-Marxism, seeing it as a product of inexorable class struggles. E.P. Thompson, in his seminal work “The Making of the English Working Class,” interprets the Industrial Revolution as an assault on workers, leading to desperate conditions that ultimately birthed the modern labor movement.

MYSTERIES AND CONTROVERSIES

Like a mist shrouded morning over a Victorian city, the Industrial Revolution is not without its mysteries and controversies. One enduring question revolves around the ‘Great Divergence’, a term by Kenneth Pomeranz referring to the economic gap that developed between the East and the West during the late 18th century. Why did the East, having shared comparable economic metrics with Western Europe up to the 18th century, not experience an industrial revolution?

Another controversy emerges in the darker aspects of the period. Some argue that the Industrial Revolution ushered in a grim era of child labour, urban pollution, and impoverishment, with historians like Eric Hobsbawm painting an almost dystopian image of the times. Others, such as Nobel laureate Robert Fogel, contend that the perceived negatives have been overemphasized, that on average, even with its challenges, life improved for many during the Revolution.

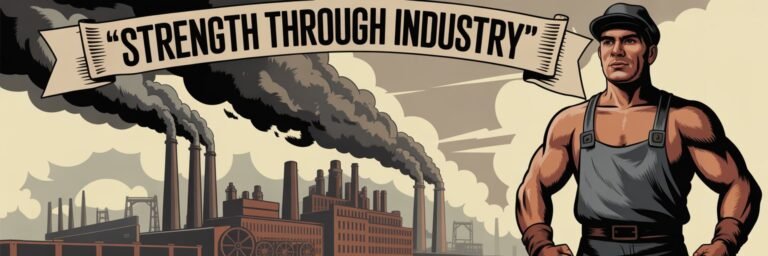

SYMBOLISM AND CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE

The Industrial Revolution was a symbol of change, of old worlds giving way to new, a concrete representation of the maw of modernity. Its machines and steam-charged factories stood as metaphors of relentless human ambition and the inexorable march of progress. The popular image of the “satanic mills” of industry, established by poets such as William Blake, was imprinted on the cultural consciousness, showcasing a dichotomy of awe and dread, a conflicted romanticization of relentless advancement.

The Revolution’s cultural significance also manifested in changes to societal structure, shifting from a predominantly rural, agricultural society to increasingly urbanized, industrial ones. This shift imbued the common public with a new sense of self-awareness and class identity, leading to significant societal changes, such as the rise of the modern labor movement.

MODERN INVESTIGATIONS

Revisting the Industrial Revolution through the lens of the present day, scholars embark on an ongoing quest to unravel the enigmas of this era. Using advances in archaeology and data analysis, researchers like Jane Humphries and Benjamin Schneider have been able to study original documents like workhouse registers and Parish records, allowing them to challenge prevailing narratives on child labor.

In the realm of the environment, historians and scientists are linking the onset of Anthropocene—an epoch marked by human activities’ impact on ecosystems—to the Industrial Revolution. The work of scholars such as Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer has flagged this as a catalyst for our current climate crisis.

LEGACY AND CONCLUSION

The resonances of the Industrial Revolution are seen and felt in every facet of contemporary existence. It reshaped our world into the urbanized landscape that we recognize today, forever altering the routines and relationships of daily life. As much as it has been judged for its detriments—exploitative labor, urban squalor, environmental degradation—it stands as the stepping stone to modern social and technological progress.

The lure of unraveling the complexities of the Industrial Revolution remains ever potent for historians, for it is not just an investigation of the past, but a mirror reflecting our evolution as a society. It serves as a testament to humanity’s inherent drive towards innovation and progress, and a sobering reminder of the trials and tribulations that accompany the march of change. This paradox encapsulated in grimy factories and gleaming cotton mills, is the enduring legacy of the Industrial Revolution—a testament to human resilience and resourcefulness in the face of relentless change. As Winston Churchill once wisely notated, the farther back we can look, the farther forward we are likely to see. Untangling the threads of the Industrial Revolution allows us a clearer vision of our past and, inevitably, our future.