INTRODUCTION

In the annals of world history, few empires have demonstrated the breadth of influence or sheer geographical dominance as the Mongol Empire. Yet it is often the individual heroes and villains within this vast dominion that capture our collective imagination. To better understand the human drama that unfolded within the great Mongol expanse, we must delve into the complex history of the key figures that shaped this epoch and question whether these so-called heroes and villains were truly as black and white as they are often portrayed.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The Mongol Empire was founded by Genghis Khan, an iconic figure in world history, in 1206. Born as Temujin, he was named ‘Genghis Khan’ meaning ‘universal ruler’. His unmatched military strategies and a well-disciplined army enabled him to conquer vast territories, stretching from Eastern Europe to the Sea of Japan, thrusting disparate cultures under his rule. Although his name often evokes images of brutality, there are historians like Jack Weatherford who argue that Genghis Khan was a progressive leader who established rule of law, freedom of religion, and promoted trade.

Following Genghis Khan’s death in 1227, his successors forged ahead, continuing his conquests and expanding the Empire. Among them, the infamous Kublai Khan, Genghis’ grandson, is best known for his establishment of the Yuan Dynasty in China. He navigated the challenging balance between upholding Mongol tradition and adopting local customs, as questioned by the historian Morris Rossabi in his book “Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times”.

THEORIES AND INTERPRETATIONS

The dominant historiographical view paints the Mongol leaders, particularly Genghis Khan, as ruthless conquerors driven by sheer ambition of territorial gain. This representation, intensified by primary accounts documenting the destruction of entire cities and sophisticated civilizations such as the Khwarazmian Empire, fuels the perception of Mongol rulers as villains.

However, an undercurrent of academic thought challenges this conventional narrative. Historians like Paul Ratchnevsky in ‘Genghis Khan: His life and legacy’ herald the Mongols’ administrative acumen and their role in facilitating East-West relationships through the Silk Road. Moreover, Genghis Khan’s implementation of a written code of law, the Yassa, established social order and justice.

MYSTERIES AND CONTROVERSIES

The Mongol Empire, shrouded in an aura of enigma and intrigue, is not without its controversies. The debate over Genghis Khan’s burial site is one such enduring mystery. According to Marco Polo and Persian chronicler Rashid Al-Din, the Khan requested a secret burial, leading to numerous speculative theories surrounding the location of his tomb.

One of the most contentious figures, Ögedei Khan, Genghis’ third son and successor, left a controversial legacy, contrasting extreme military success with disastrous personal habits. His drinking problem was even noted by his contemporaries, and his subsequent death, possibly due to alcoholism, opened a Pandora’s box of succession crises.

SYMBOLISM AND CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE

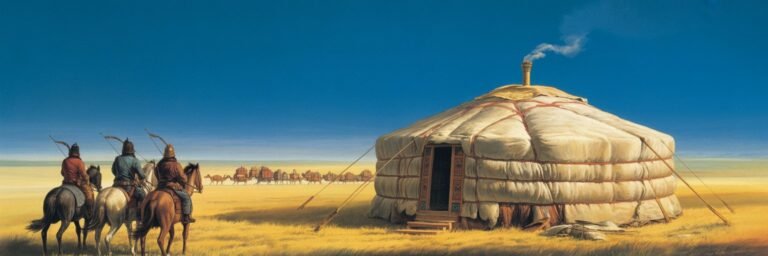

The Mongol Empire’s heroes and villains have made an indelible mark on global culture, offering a rich tapestry of symbolism and significance. In Mongolia, Genghis Khan is revered as a national icon. His image, often depicted on horseback under the Eternal Blue Sky, graces everything from banknotes to vodka bottles, symbolizing Mongolian identity, strength, and freedom.

In stark contrast, in regions once under Mongol onslaught, such as Hungary and Iran, the perception is invariably more negative. Here, the memory of the Mongols conjures up images of formidable invaders, thereby representing a traumatic historical encounter.

MODERN INVESTIGATIONS

Modern technology has ushered in a golden age of investigation for Mongol Empire enthusiasts and historians. DNA testing has uncovered the staggering possibility that Genghis Khan’s descendants number in the millions. Geneticists, like Dr. Tatiana Zerjal, have traced a common genetic marker spanning a large geographic range, indicating a single common ancestor, possibly Genghis Khan.

Archaeological endeavors like the ‘Valley of the Khans’ project employs non-invasive techniques to discover the elusive tomb of Genghis Khan. There are also resurgent attempts by historians to examine Mongols beyond the typical binary of hero/villain, recognizing the societal transformation they instituted.

LEGACY AND CONCLUSION

The legacy of the heroes and villains of the Mongol Empire remains contentious, yet inarguably enduring. They prompted a global age, catalyzing cultural exchanges, and settings foundations for international law and diplomacy. However, the shadows of their military conquests and the human toll linger on in public memory.

In conclusion, the story of the Mongol Empire is a momentous drama played out on the vast steppes of Eurasia, featuring a diverse cast of heroes, villains, and those who encroach upon both territories. As often is with history, their roles and significance are not rigid but dynamic interpretations punctuated by cultural lenses and evolving historical perspectives. As the narrative expands and challenges continue to be risen by historians and researchers, the Mongol Empire and its intricacies defy simplification, inviting us to ponder what truly makes a hero or villain against the sprawling horizon of our collective past.